Bibliography - Books

Some of the books display a style which swerves from the typical style of the author (for example the pluralis maiestatis of § 2). These peculiarities are due to definite requests of the publishers.

1. I cognomi cimbri – 136 pages, published by the author, Verona 1980.

(The Cimbrian family names.) The book is divided into two parts: in the first (about 350 entries) there is the etymological explanation of the surnames of sure or almost sure Cimbrian origin, in the second (about 240 entries) doubtful surnames are listed, some of which may be Cimbrian. Both ancient and modern family names are considered, belonging to all Cimbrian areas. In the bottom there is an Index also divided in two parts—family names and toponyms.

(Cimbrian texts—the writings of the Cimbri of the Thirteen Veronese Communes.) It is composed of the following parts: Foreword (pages 13-45); Notes of phonetics of the XIII-Communes language (pages 47-49); Texts, collecting 180 writings of several types which include the entire literature of the XIII Communes from the origins to 1960 plus a wide selection of writings from 1961 to 1979; XIII-Communes language-Italian dictionary (pages 357-389); Bibliographical sources (pages 391-399). Of many authors a short biography is given. The Foreword contains a history of the first Cimbrian settlements together with a complete survey of the many theories about their origin, including Rapelli’s point of view on the matter. The texts are followed by philological notes; the dictionary is practically a reprint of Cappelletti’s 1956 work amended from the many mistakes it contained (for which see what said in the pages 357-358).

3. Borgo Venezia (Verona): note di toponomastica – 24 pages, published by the author, Verona 1988.

(Borgo Venezia [Verona]—notes of toponymy.) 29 place names are dealth with—many of them are not indigenous of the thickly-peopled eastern quarter of Verona, but have a direct relationship with it.

4. Borgo Milano, S. Massimo, Chievo: note di toponomastica – 32 + 4 pages, 3ª Circoscrizione (Ovest) del Comune di Verona, Verona 1989.

(Borgo Milano, S. Massimo, Chievo—notes of toponymy.) 60 place names of this wide area are dealt with.

5. Nel cuore di Verona cinquant’anni fa – 96 pages, published by the author, Verona 1994.

(In the heart of Verona fifty years ago.) Little book giving a picture of how the common people of Verona lived around 1950. As the author remarks in the short foreword, several works about the Lessinia or the Bassa (‘Plain’) dwellers are available, but very few are the ones which deal with the townsmen, a negligible number of them focusing the life of the poorest. Chapters: The street; The house; The work; The social relations; The women; The dialect; The poverty, The amusement; The culture; The health; The feeding; Faith and politics; The after-effects of the war; The people’s nature.

6. Concamarise: origine e storia dei nomi di luogo – 52 pages, Comune di Concamarise, Concamarise (Verona) 1994.

(Concamarise—origin and history of its place names.) 64 local place names are dealt with.

7. Sanguinetto: il significato dei nomi di località – 54 pages, Comune di Sanguinetto, Sanguinetto (Verona) 1995.

(Sanguinetto—the meaning of its place names.) 72 local place names are dealth with.

8. I cognomi di Verona e del Veronese: panorama etimologico-storico – 504 pages, Edizioni “La Grafica”, Vago di Lavagno (Verona) 1995.

(The family names of Verona and the Veronese province—an etymological and historical panorama.) A book dealing with more than 11,000 family names present in the Veronese province, whatever origin they may have. The aim of the book is to ascertain their meaning—historical or genealogical notes are only given when they can contribute to this goal. The book is divided into the following parts: Presentation (by Giulia Mastrelli Anzilotti; pages VII-VIII); Foreword (page 1); Introduction, including Ethnical waves in the Veronese province (pages 3-9), The appearance of the family names (pages 9-15), Linguistic features of the family names—typology, morphology, phonology, lexical basis (pages 16-31); Notes for the user (pages 33-36); Bibliographical abbreviations (pages 37-44); Glossary of the terms of linguistics used in the book (pages 45-52); The family names of Verona and the Veronese province (pages 55-436); Index (pages 439-499).

The page 25 displays a map of the Veronese province showing its eight dialect areas, and in the page 27 another map of the same province shows the dh-isogloss together with the borders of the Cimbrian area—both the maps are the first ever published on these themes. The surnames come in the first place from the telephone directory, then from the local daily papers and from a number of various sources; the author has tried to take into account only those which according to his possibilities of judgment were of real residents in the province (then with exception of the military, the temporary residents, and so on).

For this work the author got the 2nd (ex aequo) prize in the 1997 cultural event ‘Lazise prize for Veneto publications’.

9. Prontuario toponomastico del comune di Verona – 224 pages, Edizioni “La Grafica”, Vago di Lavagno (Verona) 1996.

(Toponymic handbook of the Verona commune.) More than 500 place names of the whole commune of Verona—streets, squares, localities, hamlets, areas—are given here with an etymological explanation. Only historical place names, as developed from local denominations, are given—then all denominations recalling personages, towns, events, and so on have been rejected. The book is provided with about thirty illustrations concerning only historical place names.

10. Miscellanea di toponomastica veronese – 288 pages, Edizioni “La Grafica”, Vago di Lavagno (Verona) 1996.

(Miscellany of Veronese toponymy.) The book republishes 21 toponymic essays by Rapelli revised in the light of both new discoveries or hypotheses plus one unpublished essay. Titles: Villafranca; Cerro; Buttapietra; Sommacampagna; Campofontana; Siena (Villafranca); Vestenanova; Borgo Venezia (Verona); Lavagno; Borgo Milano (Verona), S. Massimo, and Chievo; Caovilla; Fumane; Illasi; Giazza; Val Fraselle; S. Bortolo; Concamarise; Sanguinetto; Buso del Gato; Biondella; Val d’Illasi; Negrar. The text is provided with a detailed index (pages 265-283).

11. I Cimbri veronesi – 72 pages, Edizioni Curatorium Cimbricum Veronense, Verona 1997.

(The Veronese Cimbri.) A popularizing work, provided with illustrations of various types imposed by the publishing house. The chapters are as follows: The Cimbri of the Roman time; The present Cimbri; The origin of the name of the present Cimbri; The first German colonies in western Veneto; The formation of the XIII Veronese Communes; The dissolution of the XIII Veronese Communes; The Cimbrian language of the XIII Communes; The life of the Cimbri; Family names and place names; Noteworthy personages; Giazza; Appendix (containing samples of the present language of Giazza); For whom wishes to know more (a little bibliographical repertory).

“It appears sure, therefore, that the first colonization occurred on the plateau where successively the Sette Comuni (Seven Communes) formed, and that it goes back at least to 1050-1100, or perhaps a little earlier.

Too bad […] any documentation on the Asiago Plateau up to the whole XIV century is lacking—a fact explainable according to prof. Sartori with the arson, for warlike or political reasons, of the archives containing the papers referring to the Sette Comuni. We have, therefore, to adopt some suppositions in order to reconstruct the history of the first community. Perhaps the first settlers, woodcutters who practised also the sheep-rearing, arrived owing to an enfeoffment promulgated by the emperor Conrad II. Around 1036 this emperor granted Onara and Romano (near Bassano del Grappa) to one Hezilo or Ezelo son of Arpon, founder of the Da Romano family, and it is possible that the new vassal placed a group of fellow-countrymen on the eastern area of the plateau.

All in all, it seems that the first Germans were called through the Benedictine abbeys. The abbeys must have held an outstanding role, in the first times, in promoting the settlement of the colonists. The abbey of Santa Maria in Organo, at Verona, was in the XI century in constant relation with Benediktbeuern as well as with other abbeys in Western Veneto (on which it probably exerted a certain supremacy, being Verona the main town of the Marca Veronese, the ‘Veronese March’). Benediktbeuern lies at about 50 kms south of Munich, and it is noteworthy that the area under its rule bordered upon the one from which the oldest group of the colonists came. Indeed, according to Kranzmayer the linguistic elements prove that the first Cimbers came from Western Tirol.”

(from I Cimbri veronesi, pages 21-22)

12. La voce etrusca e retica *peruna «roccia, parete rocciosa, lastra di pietra» – 18 pages, Accademia di Agricoltura Scienze e Lettere di Verona, Verona 2002.

(The Etruscan and Rhaetic word *peruna ‘rock, crag, stone slab’.) A paper presented in the Accademia di Agricoltura Scienze e Lettere of Verona on February 28, 1988 where an Etruscan as well as Rhaetic word is reconstructed which according to the author explains both the Veronese term prógno ‘stony stream’ and the Veronese place names Prun and Parona (with some doubts for the latter). The word is connected by Rapelli to Hittite peruna ‘rock’—an evidence, according to the author, of the link between Etruscan and Hittite. Too bad, the essay was printed in the 1997-1998 Transactions of the Accademia (pages 225-242) with an enormous number of mistakes, due to the incompetence of the typesetter as well as to the fact that for organization miscarriages no proofreading was made.

In 2002 the paper was republished in the integral original version but as a monograph, therefore with independent page numeration (from 1 to 18). At the base of the cover there is the following wording: Atti e Memorie della Accademia di Agricoltura Scienze e Lettere di Verona – 2002.

13. L’Isola dei Pagadebiti – 140 pages, La Grafica Editrice, Vago di Lavagno (Verona) 1999.

(The Cattails’ Island.) A novel set at Verona derived from a diary and narrating the life of a young man, Ezio, since 1945 (when he was eight years old) up to 1965. It was published under the pen-name Nugator, a Latin term meaning ‘who applies himself of nugae = things of little importance’.

“At the end of the day everybody went to bed early. Ezio would get out with his fellows only on Saturdays and on Sundays—in the other days one had to go to sleep early, because of the tiredness heaped up during the day and because of the lack of money. But falling asleep was not easy. When his father was alive, he returned home around nine o’clock—he did never stay outside beyond that time, and he got up always at half past six. His people were already in bed, often reading something when they did not feel sleepy. One heard the creaking of the house door, which at night was bolted, then Romano’s slow steps on the stairs, the wadded noise of his sitting on the bed, the light thud of his shoes on the floor, the tinkling of the buckle when his girdle was untied. Those slight noises seemed almost to mark the beginning of sleep—after them Ezio felt his eyelids getting heavier, and slipped almost at once into the unconsciousness. But now that Romano was no longer there, those noises were lacking. Ezio passed them mentally in review one after the other, and when he arrived at the end he began again. The tiredness forced him to seek the sleep turning on the other side, but the sleep arrived with difficulty, and when it did it was not as refreshing as before. Sometimes the remembrances made him weep silently under the blanket. And a thought creeped stealthily among all the other thoughts: ‘He will never more come back! never more!’ ”

(from L’Isola dei Pagadebiti, pages 53-54)

14. Bibliografia cimbra — 144 pages, Edizioni Curatorium Cimbricum Veronense, Verona 1999.

(Cimbrian bibliography.) It is the most complete Cimbrian bibliography so far appeared, including totally 698 titles (670 + an addition of 28). The titles are arranged chronologically and are divided in the chapters Works on the Cimbri in general (126 titles), XIII Veronese Communes (290), Seven Communes (131), Luserna (33), Other colonies in Trentino (49), Piedmont of Vicenza province (29), Cansiglio (8), Brazil (4), Addenda et corrigenda (28). The corresponding text occupies the pages 15-124. Following chapters: Index of the authors, pages 125-131 (including also editors and translators); Index of the reviews dealing with Cimbri, page 131; Index of topics (Art; Folklore, together with religion, ergology, ethnobotany, mythology; Geography, with anthropology; Literature, including the religious one, together with travel reports and bibliographies; Linguistics, with dialectology and philology; History), pages 131-132; Index of chapters, page 133. The book is opened by a Foreword by Maria Hornung (in Italian, a translation by Rapelli, pages 5-6; in German, pages 7-8).

Remarkable features of this work are: 1) only the first editions of any essay or book are quoted; 2) the translation (within square brackets) of all titles in any non-Italian language, except those in Latin; 3) the comment given to most works (in order to explain their content, when the title is not clear enough; in order to give the approximate number of the entries, when speaking of dictionaries; in order to inform about reprints containing some modifications, and so on); 4) the books containing several essays and the books of the Transactions are not quoted as individual books, as each title of the essays is given separately. In this Bibliography, anyway, the articles appeared in the reviews dealing with the Cimbri are not quoted (with exception of those of particular importance), in order not to make too heavy the book.

An appendix of the book appeared under the title Bibliografia cimbra (Supplemento I) in CT no. 23, 2000, pages 121-127. Other 19 titles are here quoted; too bad, for a mistake of the printing-house the indexes of both the reviews and the topics are missing, while the authors’ index quotes only five names. In the no. 24, 2000 of the review (pages 162-163) the said missing material has been published.

15. Proverbi italiani: pillole di saggezza popolare – 192 pages, Demetra, Colognola ai Colli (Verona) 2000.

(Italian proverbs—pills of folk wisdom.) A book in which over 800 proverbs of all Italian regions are collected and explained, classified into 11 sections (“Man, woman, love”; “Family and the house”, “Work”; “Eating”; “Religion”; “Social relations and politics”; “Money”; “Animals and plants”; “Life, death, and health”; “Meteorology”; “Miscellany”). Each proverb is quoted in the form it has in the local dialect, followed by its translation into Italian and almost always by a comment.

16. Si dice a Verona: 500 modi di dire del veronese – 192 192 pp., Cierre Edizioni, Sommacampagna (Verona) 2003.

(So they say at Verona—500 turns of phrase of the Veronese dialect.) Here 517 turns of phrase of the Veronese dialect are listed, mostly collected at Verona downtown. Rapelli means with “turn of phrase” an expression which would not have an understandable meaning if literally translated—a sentence, or sometimes even a single word, which is used with a quite particular meaning. Here we have to do mostly with metaphorical pictures, in some cases with remnants of old expressions, which sometimes are very ancient. Of each expression both the present meaning as perceived by the speakers and the literal meaning are given—many expressions are explained etymologically.

The books is composed of: Presentation by Dino Coltro (pages 9-10); Introduction (pages 11-17); List of the abbreviations (pages 19-20); The turns of phrase (pages 23-159); Notes (pages 161-178); Index (pages 179-189).

“El d’à fato pèso de Ninéta — Literally, ‘he did all sorts of mad things worse than Ninéta’. It is said of a person who did all sorts of mad things, who played all sorts of pranks, speaking above all of children. The expression, which is widespread in the whole province but was originally of the Veronese Lowlands, derives from a real person. One Francesco Nesi called Nineta, born at Isola Rizza, was designated by the royal superintendent De Lederer in a 1822 poster as a robber to be seized and brought to justice. His wife, too, was pursued in another poster as his accomplice. According to the legend he pretended to speak to some partners, while in reality he pillaged his victims always by himself, and he would have been a Passator Cortese-like adventurer rather than a hardened criminal.

“A similar locution is farde peso de Bartoldo ‘to behave worse than Bertoldo’. This is however a learned expression, referring to the gags of Bertoldo, a buffoon at King Theodoric’s Court, as narrated in the booklet Bertoldo by Giulio Cesare Croce (1550-1609). This locution, on the other hand, has entered also literary Italian.”

(from Si dice a Verona: 500 modi di dire del veronese, page 75)

17. Nel cuore di Verona: gli anni Cinquanta dei veronesi – 140 pages, Cierre Edizioni, Sommacampagna (Verona) 2003.

(In the heart of Verona—the 50s of the Veronese people.) The little book is essentially a reprint of the work listed above under the § 5 (Nel cuore di Verona cinquant’anni fa), with some modifications and additions. Among the latter, the hint in the foreword to the causes of the forced depopulation of the historical center from about 1970 and the insertion of several pictures are remarkable. The pages 131-132 give a short author’s biography.

“The aged were not as numerous as nowadays. The illnesses mowed them down one after the other, especially the TB. Due to the lack of antibiotics, the only possibility one had to overcome this terrible sword of Damocles lay in his physique—if it was strong one survived, else he died. The infirmities of old age were accepted by the family as an unavoidable component of life. One felt pity for the semi-paralyzed or arteriosclerotic grandparents, and daughters, daughters-in-law, and grandchildren took turns to help them. Seldom somebody went so far as to complain of the troubles that a grandfather or a grandmother could cause—apart from the general respect for the older people, the family was regarded as a whole, from the newly born to the founder who set out to the end. No husband’s mind, no wife’s mind could have been crossed by the idea of telling their partner ‘your father or your mother have nothing to do with us’. The aged were taken to the home of Via Marconi only when attending to them was by no way possible because of a too developed arteriosclerosis. Then the daughters approached an attendant and gave him weeping some money in order that he treated with respect her parent. Later on they would have paid a visit to him or her every two or three days. Sometimes the old mother or the old father shook for some moments out of their unconsciousness and looked terrified and incredulous at the room where they were, imploring their relatives to take them away from that house, to make them come back home. This added torment to the torments. The hospice was regarded as little less than a jail, due to the inhumanity of the treatment given. There the old man lost his identity of father, grandfather, uncle, great worker, honest person, veteran, and so on, to take that of a rag-doll. The attendants addressed everybody as tu (thou) in a time when the tu was only familiar and at any rate required an explicit authorization, and the people raged when heard them addressing that way their beloved. Often the personnel left a couple of hours or more the aged steeped in their own stools or in their own urine, or gave them a food now cold. The attendants had some rights to vindicate (they were few and ill-paid), but this did by no way attenuate the unpleasantness of such events.”

(from Nel cuore di Verona: gli anni Cinquanta dei veronesi, pages 105-106)

18. I cognomi del territorio veronese – 858 pages, Cierre Edizioni, Sommacampagna (Verona) 2007.

(The family names of the Veronese territory.) This book is practically an up-to-date remake (up to May 2007) of the book listed above under the § 8. The Presentation is by Maria Giovanna Arcamone, of Pisa University. Many etymologies are revised (taking into account both new data and the books appeared in the meantime on Sardinian, Friulian, Modenese, Sicilian surnames), with about thousand new surnames and a mass of ancient documentation lacking before. The family names dealth with amount to about 12,000, of whom approximately the 60% belongs to people residing in the province of Verona and the rest concerns family names not present in it but quoted as a support of the etymological explanations proposed. The Foreword has been enriched with a number of new remarks.

“Among the first Veronese surnames we can list: Sambonifacio, denomination of an important family whose founder was Milone di Sambonifacio count of Verona, dead after 955 (it is, however, noteworthy that Milone is never recorded in the contemporary documents with such a family name, which therefore appears to have been attributed to him only successively by the historians—actually, the first personages defined in the documents with the surname Di Sambonifacio are the brothers Enrico and Uberto, around the middle of the XI century); Erzoni, whose founder is one Herizo recorded between the third and the fifth decennium after 1000 (the Erzoni family is said domus de Herizonibus around the middle of the XII century); Della Scala, whose oldest quotation is of 1053; Turrisendi, a family recorded from the XI century; Crescenzi, a family which emerges politically at the beginning of the XII century; Avvocati (some personages so named appear in 1185); Monticoli or Montecchi, a family which around the end of the XII century leads the Veronese Ghibellines; Dalle Carceri, a family known from the middle of the XII century. No one of these surnames survived until today.

Even in the Veronese area the custom of the surname spread to the whole populace very slowly. In 1239, […] among the exiled Guelphs there were persons with a surname and persons without it, although they belonged to the nobiliary class or to other higher classes. However, a century later the surname process appears practically fulfilled in the upper classes. The thirty-eight milites displayed by Cangrande in the 1328 chivalrous curia, the most splendid among the Della Scala’s curie, are all endowed with family names.”

(from I cognomi del territorio veronese, pages 33-34)

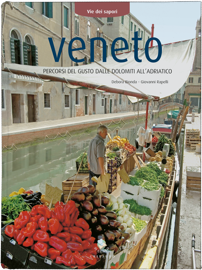

19. (together with Debora Bionda) Veneto: percorsi del gusto dalle Dolomiti all’Adriatico — 280 pages, Edizioni Gribaudo, Milan 2009.

(Veneto—routes of taste from the Dolomites to the Adriatic Sea.) This book offers a detailed survey of the great Veneto’s oeno-gastronomic tradition, and lays stress on the evolution of the culinary art through recipes signed by the best chefs of the area. Rapelli gives here a description both historical and artistic of each Veneto’s province. The texts are the following: Venice, pages 35-45; Verona, pages 77-88; Vicenza, pages 133-143; Padua, pages 165-175; Treviso, pages 187-197; Rovigo, pages 223-229; Belluno, pages 241-249.

20. La lingua veneta e i suoi dialetti — 116 pages, Perosini Editore, Zevio (Verona) 2009.

(The Veneto language and its dialects.) A popularizing little book that illustrates the history of the Veneto language and its dialectal varieties from the river Mincio through the Bocche di Cattaro (the Bay of Kotor). The first part (pages 1-47) deals with the present relation between Italy’s official language and the Italian dialects.

The book is divided into: The language of family and of one’s affections (foreword by Giancarlo Volpato, pages 7-19); Introduction (pages 23-24); The Italian dialects (pages 25-47); The Veneto identity (pages 48-62); Elements of linguistic history (pages 63-69); Main features of the Veneto language (pages 70-77); Veneto influence on Italian (pages 78-84); Veneto influence on other languages (pages 85-89); Words introduced in Veneto from other dialects or languages (pages 90-94); The jargon (pages 95-97); The lingua franca (pages 98-99); Veneto communities in the world (pages 100-104); Biographical note (page 105); Bibliographical outline (pages 106-111); Index (page 113). Two maps illustrate the spread of the Veneto dialects at the time of the French invasion at the end of the XVIII century—one being limited to the Veneto proper, the other displaying the area from Trieste to the Bay of Kotor.

“In conclusion, let’s be fond of the dialects—all dialects, of any Italian area. They not only serve to give vent both to our emotionality and our creativity, they are useful as well to the official language, because they are an inexhaustible tank of new expressions, new terms, new ways of thinking and communicating. Here much can be done through the pattern, using the dialect at home or among the friends, keeping alive the particular phrases heard from the aged. Like in many other fields of life, even in this one what is really important is the pattern we display. The young look at us, and often they reproduce instinctively our behavior. It is of no use that a thief warns his son not to steal, or that an anticlerical says he doesn’t forbid to his son to go to church. If the children see that a value is neglected, they too will be inclined to neglect it.”

(from La lingua veneta e i suoi dialetti, page 42)

21. Si dice a Verona: 550 modi di dire del dialetto veronese — 192 pages, Cierre Edizioni, Sommacampagna (Verona) 2013.

(So they say at Verona—550 turns of phrase of the Veronese dialect.) A new edition of the 2003 book (see the § 16), with the addition of 33 new expressions.

22. Il latino dei primi secoli (IX-VII a.C.) e l’etrusco — 230 pages, “ItaliAteneo”, Società Editrice Romana, Rome 2013.

(Latin of the first centuries [9th-7th bc] and Etruscan.) This book proposes a lot of new etimologies of Latin, starting from an assumption—the Latin shepherds came to Rome in the ninth century bc in a completely Etruscan area. The contact of the Etruscan natives with the newcomers—shepherds and sometimes farmers—was traumatic; the future, wonderful Latin culture cannot be explained out of such an assumption. The newcomers encountered a people highly experienced in metallurgy, who introduces the use of iron in Italy (and from Italy, later on, in both La Tène and Hallstatt), but a people also experienced in the art of navigation, in hepatoscopy, and in town-planning.

“All of the scholars, bar none, have acknowledged that the Etruscans have exerted a strong influence on the Romans. However, the insufficient knowledge of the Etruscan language had not allowed to obtain a detailed picture of such an influence. One dwelt almost exclusively upon the orientalizing period of the Etruscan culture, upon the seventh and sixth centuries bc, when it reaches its climax (copying the Greek models of sculpture and architecture and developing an astonishing goldsmithery) while in the same time Rome knows the rule of the two Tarquinii (two kings who in reality were perhaps only one). But I think one cannot have doubt about the arrival of the Etruscans on the banks of Tevere very earlier, in the frame of their first expansion in the Italian peninsula. They spread initially wherever they could find minerals, in particular ferriferous ones. Their culture was by far superior to that of both the Umbrian and the Latin shepherds, and these could not avoid to absorb a lot of elements from it.

(...) In favor of an early Etruscan influence speaks the toponymy of the Rome area, surely preceding the arrival of the Latins (Suburra, Palatium, Tiber, the very name of Rome). Even the huge number of Latin personal names of Etruscan origin speaks in favor of a successive insertion of Latin pastoral tribes on an Etruscan people—the contrary could not be acceptable.”

(from Il latino dei primi secoli (IX-VII a.C.) e l’etrusco, pages 162 and 165)